ExtraTerrestial Intelligence (SETI), and the

basic idea was to turn the problem around and figure out what an

extraterrestrial radio astronomer could make of the Sun/Earth

system.

ExtraTerrestial Intelligence (SETI), and the

basic idea was to turn the problem around and figure out what an

extraterrestrial radio astronomer could make of the Sun/Earth

system.Before our work on the Virgo Cluster [see

Backstory #1],

I also worked under Dr. Sullivan on another project, along with

another student. It was on the Search for

ExtraTerrestial Intelligence (SETI), and the

basic idea was to turn the problem around and figure out what an

extraterrestrial radio astronomer could make of the Sun/Earth

system.

ExtraTerrestial Intelligence (SETI), and the

basic idea was to turn the problem around and figure out what an

extraterrestrial radio astronomer could make of the Sun/Earth

system.

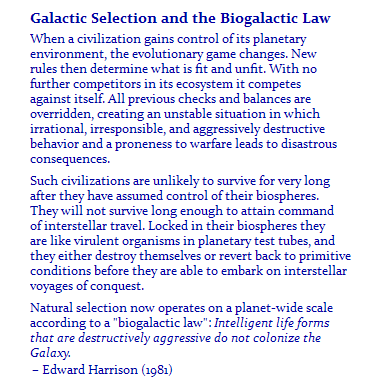

This was just a few years after Carl Sagan's best-selling book "Cosmic Consciousness" had first really brought the idea of SETI to large audiences (c.1974-5), even though it had been more than fifteen years by then since Frank Drake's Project Ozma search. Sagan had been second author on the 1966 book "Intelligent Life In the Universe", with Iosif S. Shklovski, based on the latter's 1962 book "Universe, Life, Intelligence", so Sagan's interest in this area went back at least a decade.

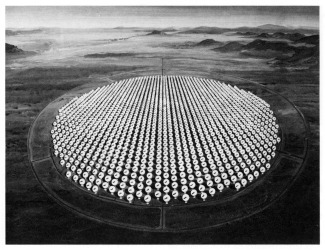

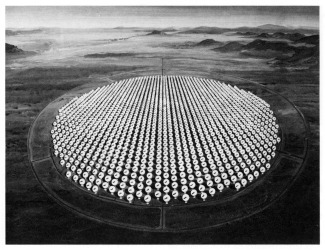

Radio astronomers of the time were proposing and lobbying for the Cyclops Array, which was envisioned, like in the artist's conception at right, as consisting of a thousand or more 100-meter dishes, more than 100x the collecting area of the Arecibo radio telescope. Cyclops could detect a suitably pointed copy of Arecibo aimed at us out to several kiloparsec distances, say 3 kpc. Cyclops could detect itself out 10x further (the square root of the 100x gain in photon collecting area), and 30 kpc, being the diameter of a typical galaxy, means a Cyclops sized telescope could detect itself anywhere in the galaxy -- again, if it was pointed at us. A gigawatt omnidirectional beacon at a distance of ~300 parsecs yields a flux at earth of one photon per second per square kilometer at around 1½-2 GHz frequency, so you need a lot of square kilometers in the radio part of the spectrum because the waves are so big.

The hitch was the cost was immense: something like 20x the initial appropriation for the Hubble Space Telescope, and maybe 4x what the HST eventually cost. On the other hand, roughly two-thirds or three-fourths the cost would have been just for the steel to build the structures, and at that time the U.S. steel industry was in a funk and severe down cycle, and could have used the business. 1977 was when the first of the steel mills in Youngstown, OH, closed, and over the next few years the town of 170,000 lost 50,000 steel industry jobs; Bruce Springsteen had famous songs about this. I suppose today it would make sense to build Cyclops on the far side of the moon, from radio interference considerations. As long as you're going to spend a gazillion dollars to do something you might as well spend several gazillion to do it right.

Anyway, then Carl Sagan came to campus. The occasion was the big annual science lecture at the University of Washington, and Dr. Sagan was a really big "get". He was then at about the height of his fame, even though the Cosmos TV series was still several years in the future. He'd become a de facto spokesman for the Space Age and Planet Earth over nearly a decade of occasionally appearing on Johnny Carson's Tonight Show, though by then the media would go to him on just about any space related story before going to NASA spokespeople because he was so well known.

So when the announcement was made on campus of his upcoming appearance, Dr. Sullivan wrote to him, told him about the SETI work we were doing (thinking he'd be interested - he was), and a meeting during his visit was arranged.

Unfortunately, when he got to campus the day of the lecture he ended up getting stuck in the Geophysics and Planetary Sciences Department all afternoon, which (along with Atmospheric Sciences) was in a different building some distance across campus from the Astronomy Department. The latter at that time occupied one end of the 2nd floor in the old (and big) Physics Building, just north of the fountain -- which was empty of water, for renovation or something, for what seemed like a long time, a year or more). The meeting was going to take place in Dr. Sullivan's small office there.

After the appointment time had gone by there was a phone call from someone over in the Geophysics and Planetary Sciences Department saying Sagan was delayed, but hadn't forgotten about us. Then a half hour or something like that later there was another such call, and after the third or fourth of these the meeting simply had to be cancelled, since he had to get to dinner and prep for the lecture only a few hours later.

The underlying cause was that the Viking 2 lander had touched down on Mars only a few months earlier and there were lots of new results to share and discuss with his colleagues in that area. Sagan was, after all, Director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Columbia, so while not having our meeting was a minor disappointment it was understandable, and all for the good of science. Needless to say, he packed the 800+ seat huge lecture hall and gave a phenomenal presentation. It's right up there with having gotten to see Frank Zappa (the night of a lunar eclipse), Smokey Robinson, and Pete Seeger with Arlo Guthrie -- not to leave out John Denver, Devo, or Captain Kangaroo!

I also shouldn't leave out that Hans Dehmelt's "|g|-2" lab was on the first floor of the Physics Building, and the door was often open so you could look in while walking by, or at least hear the soft hum of all the vacuum equipment running. Probably my senior year I saw the flyer on the bulletin board for what turned out to be a rather nice departmental lecture he gave on what all they were doing, and it wasn't a big surprise when he shared in the Nobel Prize a decade later.

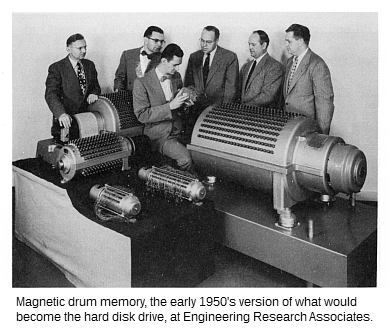

Well, our SETI work was eventually completed and published in Science magazine about a year later. The particular issue is, in fact, an obscure collector's item -- but not for our paper. Rather, it had a 3+ page special feature, by William D. Metz, on Seymour Cray and the Cray 1, the world's first famous supercomputer. It still makes for great reading -- but then I was part of the last generation to go through high school working science problems on a slide rule. (Yes, we considered ourselves quite advanced compared to those before us who only had an abacus. Four function calculators existed but were the price of a new top-shelf phone today -- there was only one kid in my school who had one -- though by the time I graduated HS a scientific calculator could be had for only maybe 50-60% more, and only a few years later the programmable HP-25 was magic that could be had for probably about $1500-2000 in today's money. Not long after they were giving away four function calculators for free with a fill-up at the gas station.)

"Midwest Computer Architect

Struggles with Speed of Light" (Science, vol 199; 27 Jan 1978;

pgs 404-409).

Note the early expression in a slightly different form of what

later would be known more widely as Moore's Law.

[The Cray-1 ran with a CPU clock speed of 250 MHz, or at least 10x less than laptop CPUs of ~3 decades later. But even this was unimaginable to "personal computer" (PC) owners of about a decade later. The first Commodore Amiga, for example, using the same Motorola 68000 CPU as the Apple Macintosh, ran at all of 1 MHz. I still remember when a friend and associate in the local astronomy club got a new Intel 386 PC, c.1993, which ran at 25 MHz, and what a screamer it seemed to be. By the time the World Wide Web, Netscape, and AOL became big in 1995-6, the popular machine was a 66 MHz 486. Anyway, one clock cycle at 250 MHz is 4 nanoseconds, so light (in a vacuum) travels about 4 feet during that length of time (yes, the speed of light is ~1 foot per nanosecond), and this is also about the speed at which an electrical signal travels in a wire. The Cray-1 was built in a semi-circle to keep the wire lengths to about 4 feet.]

By a strange coincidence, Cray and I were both living in Colorado Springs at the time of his fatal car accident. I knew exactly the often troublesome interstate exit and interchange where it happened, the exit off I-25 to the south gate of the Air Force Academy. As it turns out, Dr. Sullivan also had a Colorado Springs connection, having been born there.

As far as our SETI work went, forty years later it's actually the best of both worlds: whenever the topic comes up, in books or on the radio, say, our basic result is almost always mentioned in the introductory comments as something "everyone knows". Neither our paper nor us is ever mentioned, so it's like having introduced an idea or meme into the wider culture, while we stay nicely anonymous for having done so. While there's a lot of science done with a limited shelf life, I think one of the things I picked up from Dr. Sullivan was the notion of doing really definitive work, so it only has to be done once, and in that I think we succeeded, since no one has really ever challenged it or felt they had to do it over the "right" way. It still stands out there as an important result, with few modifications necessitated by changes in the interim.

A non-technical version of our work appeared more than a year after the Science paper: Eavesdropping on the Earth.

[The Brian Eno quote at the beginning of the paper is an excellent

example of misheard and mangled song lyrics.

It should read:

"Nobody passes us in the deep quiet of the dark sky

Nobody sees us alone out here among the stars

No one receiving the radio's splintered waves".

(from Before and After Science, 1977). ]

The Mercury issue cover photo? That's Io as seen by Voyager 1, where sulfur volcanoes had just been discovered during its flyby of Jupiter on March 8th.

The full technical paper in Science Magazine is available via the SETI Institute: Eavesdropping: The Radio Signature of the Earth.

And, if you want to see a few seconds of the computer graphics animation I made, a few frames of which were on the Science cover, you need to watch PBS TV's Nova science show from 1986. I'm referring to the episode hosted by the famous Lily Tomlin, titled Is Anybody Out There?. Nova's archive doesn't go back that far (only to 1996) but I noticed someone had made it available on YouTube since I first put this page up. The animation/movie we jokingly referred to by the name "As the World Turns" is about 34:45 in, followed by almost a minute of an interview with Woody. Be sure to stay through the credits, as our names run -- just before Jill Tarter. The episode is notable for lengthy statements by such luminaries of the classical age of SETI as Frank Drake, Phil Morrison (see below), Bernie Oliver, and Carl Sagan.

If roughly the current level of total broadcast TV power was first reached in the late-1950's (Figure 7 of the paper), then as of ~2018-20 the expanding bubble of radiation now extends out to ~20 parsecs from earth and includes ~1000 stars. With this average space density of stars in the sun's neighborhood, about four dozen new stars (46) are being added to this bubble each year, or just a little less than about one per week (0.88) -- one every eight days on average.

What this means, if I was King of SETI, is that I'd be looking intensely for replies, or some other indication that our radio emissions had been detected in some way, from the ~100 stars at about half that distance or a little less, say 25-30 light-years out (8-10 pc).

[Where does the 1000 stars within 20 pc value come from? In

the Jan 2019 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine there's

an article (pg. 34, by Keith Cooper) on the nearest stars. Within

10 pc there are a total of 378 stars in 317 systems. Since

the 20 pc volume is 8x that of a 10 pc radius sphere, this would

scale up to over 3000 stars in the larger volume.

However, 21 of the 378 are white dwarfs, which presumably are

not candidates for possibly hosting an evolved, technological

civilization, not that it's impossible. A 2003 article on white

dwarfs in Annual Reviews of Astronomy and Astrophysics

says there are 109 known white dwarfs within 20 parsecs (page

473), so the 8x scaling up is not quite perfect, but it also

says this number is only believed to be complete to ~13 parsecs;

older, cooler, less luminous WDs would be too faint to detect

in the surveys, and as well there's a statistical certainty

that some would have no (or very little) component of their

space velocities across our line of sight and thus would not

be detected in any proper motion survey.

In addition, 284 of the 378 (yes, 75%) are M dwarfs, most of which

are also probably unsuitable, for two reasons. First, due to their

low luminosity the size of their habitable zones, where an orbiting

planet is at the right temperature for liquid water to exist (the

"Goldilocks Zone"), is rather small. Second, such stars tend to be

quite active, in the sense of having significant solar flares and

the like; this is thought to be problematical for the evolution and

development of life over long time scales for several reasons --

for example, planetary atmospheres can be stripped away. However,

recent studies have seemed to indicate this flare activity may be

at high latitudes on the star, so if its planets orbit in its

equatorial plane they may not be as affected as previously thought.

Yet another downside for planets around low-mass stars like this is

that they would have to orbit so close to their suns to be in the

habital zone that their spins would likely be tidally locked in a

resonance with their orbital perioed, causing them to always have

one side facing their star; any atmosphere would then almost

certainly freeze out on the dark, cold side of such a planet.

So if we reduce or de-weight their numbers by 90%, essentially

counting only the brightest and most stable 10% of the M dwarfs,

then the remaining 28 M dwarf stars add to the 73 stars within 10

pc with spectral types A through K to yield a net total of right

around 100 viable stars within 10 pc. This would scale up to there

being 800 suitable stars within 20 pc, not 3000+.

But... the sample is not complete. The article says the sample

for the nearest 500 stars is thought to be 90% complete, but the

completeness percentage drops as we go to farther distances. Time

and further observations and analysis will tell for sure, but if

we simply take the completeness as being 80% out to 20 pc, then

the total is 800/0.8 = 1000.

The caveat is this: completeness issues affect lower luminosity stars,

the white and later type M dwarfs, almost exclusively; all the A to K

main sequence stars within 20 pc have almost certainly already been

found because they're relatively bright. So a more conservative number,

and one which doesn't add in some small percentage of M dwarfs, would

be something like 75*8 = 600 stars. As is commonly said in astronomy,

what's a factor of (almost) two among friends?

The caveat is this: completeness issues affect lower luminosity stars,

the white and later type M dwarfs, almost exclusively; all the A to K

main sequence stars within 20 pc have almost certainly already been

found because they're relatively bright. So a more conservative number,

and one which doesn't add in some small percentage of M dwarfs, would

be something like 75*8 = 600 stars. As is commonly said in astronomy,

what's a factor of (almost) two among friends?

According to the people analyzing the data from NASA's Kepler

exoplanet mission there should be about four earth-like (rocky)

planets in habitable zones within 10 pc, which scales up to ~30

(give or take a few) within our expanding bubble of radio

radiation.]

Anyway... anyone who reads "Eavesdropping on the Earth" might have been struck by the similarity between what in the paper are called "acquisition signals", and the recently discovered Fast Radio Bursters (FRBs).

I heard Seth Shostak, of the SETI Institute (somewhat ironically), mysteriously claiming that these mysterious objects are at great distances, like several billion light years, and therefore have to be intrisically extremely luminous objects to be visible out at this distance (9/30/2019). I don't know how he knows this, since virtually nothing is known about FRBs other than their existence. The extragalactic radio sources turned up in the surveys of many decades ago consist of radio galaxies and quasars with a typical distance of several billion light years, but there's no reason to suppose FRBs are part of this population.

I suppose Shostak is reasoning along simple, standard lines: that because the FRBs that have so far turned up appear more or less uniformly distributed around the sky (the technical term is "isotropic", meaning the same number, approximately, in all directions), rather than being confined to the plane of the Milky Way, that they must be far outside the galaxy and not associated with it. However, the galaxy is several hundred parsecs thick, so if instead the FRBs were at distances of only tens or dozens of parsecs they could also appear isotropically distributed on the sky, because they are so close. This is exactly the case with complete samples of nearby stars, like within 10, 20, or 50 parsecs, say. Samples with an order of magnitude greater extent will start to show the flattening associated with the density fall-off perpendicular to the plane of the galaxy, but it takes a much larger number of stars to show this. The number of known FRBs is nowhere up in this range at this point.

This is not to suggest the FRBs are necessarily us looking at military radars on distant planets like we have on earth. They could be any sort of local service with quasi-random characteristics, like a system of Space Traffic Control signaling beacons, to name but one possibility. Remember, you heard it here first. But basically we don't know what they are or why they're there, just like the cause of our military radars would be a mystery to a radio astronomer on a distance planet.

The always borderline outrageous Avi Loeb had this to say about FRBs in Scientific American in June 2020. Another of his opinion pieces there worth reading, from about a year earlier, is Are We Really the Smartest Kid on the Cosmic Block?

Eavesdropping on radio broadcasts from galactic civilizations with upcoming observatories for redshifted 21 cm radiation, Abraham Loeb and Matias Zaldarriaga; Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, Volume 2007, January 2007. (Abstract only)

The really notable person I did meet as a result of my SETI work was Philip Morrison. A student of J. Robert Oppenheimer, he'd worked on the Manhattan Project and was, in fact, the person who drove the plutonium core for the Trinity Test from Los Alamos down to the site -- in the back seat of a Dodge sedan -- the minimum critical mass of which he'd been involved in determining. He was all of 29-30. There was only one follow-on car, in case of a breakdown, since they didn't want to draw attention to what they were transporting. This was practically all the plutonium from the Hanford reactors they'd generated and extracted (manufactured) up to that point, and in today's money it had probably cost on the order of at least $10 billion to come by. It wasn't explosively dangerous, though it was radioactive, only the kind that a lead-lined box bolted to the floor was sufficient to make safe. People who handled the core described it as being warm, like holding a bunny. It was, in fact, in two parts, two hemispheres, which were nickel plated to absorb most of the alpha radiation. There were two halves so the initiator could be installed in a small pit at the center of the core as the bomb was being assembled for the test. Morrison was at the main/south bunker, 10 miles distance, from ground zero, along with the top brass. He said he was struck by the heat: they knew, of course, that the explosion would be bright -- that was why they had welder's glasses on -- but in the cool, morning desert air he said it was like someone had opened an incredibly hot oven door. After the Trinity Test, Morrison was part of the small crew sent from Los Alamos to Tinian to help with bomb assembly before the Enola Gay and Bockscar B-29's were loaded and sent towards their targets. As someone stationed forward, he was part of the first crews to survey the damage weeks after. Later he became a physics professor at MIT.

Besides also being a pioneer in gamma-ray astronomy, and a science educator (his writings appeared in Scientific American magazine over a nearly thirty year period), Morrison also wrote a seminal paper in Nature in 1959 with Giuseppe Cocconi that proposed the potential for microwaves (GHz frequency radio waves) in the search for interstellar communications.

So... 7 or 8 months before our paper appeared in Science, when it was hardly even an outline of a rough draft, there was a SETI conference at JPL in Pasadena. Dr. Sullivan had heard about it, had arranged to get on the program -- we'd spent almost a year on our research at that point -- and he'd gotten travel funds to go. Then, as it turned out, he and his wife were expecting their first child at the very time of the conference, and at the last minute he decided it better to send me instead. I was only an undergrad junior, so my presentation was pretty bad. I only had a day or two to prepare, and had never done anything like that before. But I got to stay at the Pasadena Hilton, and it was on the shuttle bus from there over to JPL in the morning that there I was by chance sitting across from Dr. Morrison in the facing seats. I didn't know who he (or anyone else) was then, and I don't recall now what we chatted about during the ten or fifteen minute ride, but he was both very amiable and obviously quite astute; his wide-ranging depth and range of knowledge was obvious no matter what he was talking about. Someone later pointed out to me that that was the Phil Morrison, from MIT and Scientific American. I didn't read Scientific American -- for one thing there was no time as an undergrad taking 16 or 18 credit hours, and for another it was over my head unless the article was right down my alley and was on a topic I already knew something about. Morrison was clearly an extraordinary intellect, even just on a first meeting.

At a NASA conference entitled "Life in the Universe", held at the Ames Research Center in June, 1979 -- "not only the largest but the most diversified meeting ever held in this general domain" (Philip Morrison) -- Woody (Dr. Sullivan) gave a short synopsis presentation "Eavesdropping Mode and Radio Leakage from Earth" summarizing our work.

From an astrophysical point of view, perhaps the most interesting talk/paper now was that by David C. Black on Prospects for Detecting Other Planetary Systems. But not so much for what it covers, but rather for what it quickly brushes over, namely the currently popular method of transit photometry:

Another possible observable manifestation of a planetary system involves the transit of a star by a planetary companion. During a transit, the planet passes between the star and an observer and blocks out part of the starlight. The associated apparent dimming of the star could, in principle, be detected with very accurate photometric observations. Because this technique for detecting other planetary systems is somewhat limited, we will not discuss it further here.

It's not clear exactly what limitations he has in mind, but two come to mind. For one thing, the orbital plane of the planet has to be nearly coincident with our line of sight so that a transit occurs in the first place. From surveys of stars it was known what fraction are eclipsing binaries, or, more precisely, what fraction of binaries are eclipsing binaries. The situation here for something that can be seen in a light curve is more favorable than in the case of planets, because a companion star is larger than a planet so an eclipse (transit) is more likely to occur. A star could have a planetary companion but it would not be detectable by this method if the plane of its orbit is not right. So the odds may not have seemed favorable.

The second consideration has to do with the need for "very accurate photometric observations". At that time, the general standard for ground-based photometry (of stars, primarily) was an accuracy of 0.01 magnitudes. This works out to ~1% accuracy, or a signal-to-noise ratio S/N=100.

Ignoring all other sources of noise in some generalized photometric system, photon statistics alone tell us we need to detect at least 10,000 photons from the star to achieve the desired level of accuracy, since the photon arrival time noise ("clumpiness") is equal to the square root of the number of photons.

For a situation like that of Jupiter and the Sun, the planet is about one tenth the diameter (or radius) of the star, so the area of its disk is only ~1% that of the star's disk, since the area goes as the square of the radius. Thus, a transit of the Sun by Jupiter as seen from a suitably located distant observer would result in a dip of only about 0.01 magnitudes. In order to detect such a small dip in the light curve we'd need better than 0.01 magnitude accuracy. An S/N=10 for the dip would mean we'd need 0.001 magnitude accuracy, which requires us to detect 100x more photons -- a million versus ten thousand. So a ten times bigger telescope diameter is needed.

By the way, for a star the mass of the Sun and a planet that size at Jupiter's distance of 5.2 AU the transit takes ~28 hours, which only happens once every 11.86 years, or only about 0.027% of the time (1:3700). In the more likely case that the inclination of the planet's orbit is not exactly dead-on at zero angle towards us, the transit will take place more quickly since its path is traversing the chord of the star's disk, so the odds are even longer. This is the motivation for looking at huge numbers of stars all at the same time, as the only way to multiply the long odds.

For a planet the size of Earth, which is ~10x smaller in diameter than Jupiter, the situation is that much worse. For a transit of Venus (about the same size as Earth), the dip is only about one part in 10,000, or 0.0001 magnitude. To get S/N=10 for the dip we need 0.00001 magnitude noise, or at least 10 billion photons from the star.

One might wonder what the effect of twinkling is on ground-based photometry, since to the eye it makes the brightness of a star appear to flucuate drastically, adding to the noise. It turns out not to matter much with a telescope bigger than about 8-10" in diameter, since the effect of twinkling there is to make the star jitter in position slightly and/or change in apparent size. So long as the photometer aperture is big enough all the light from the star is measured even if it jumps around in position a little or "blows up" in size during the periods of worse "seeing". The only penalty is that a larger photometer aperture includes more night sky background light (the reading of this alone is subtracted from the star+sky reading to give the star's measure), which means it will be slightly noisier, but even with this the other sources of noise in the system might still be more significant.

Anyway, so what happened to all this building interest towards a real radio astronomy SETI search effort back in the 1970's? The kibosh was put on it by a Senator from Wisconsin (Proxmire), in an early example of what's now called "cancel culture". He'd achieved a sort of national political folk heroism for his "Golden Fleece Award", issued monthly from March 1975 to December 1988 -- behavioral scientist Ronald Hutchinson sued Proxmire for libel and requested $8 million in damages in 1976. These "awards" were Proxmire's way of calling attention to what he considered outrageous and wasteful government spending (like the $800 toilet seats you've no doubt heard about). Even though he was a notorious hawk and always voted for increased military spending, one of his favorite targets was the Navy; duh, there are no Navy bases in Wisconsin.

In 1979 he singled out NASA's proposal for spending $2 million/year on (foolishly) searching for "little green men". This SETI expenditure would have been ~$10 million in today's money, most all of it going to travel costs (airline flights, hotel rooms, etc.) for the various conferences and study groups on the topic that NASA helped organize and/or hosted. In other words, there was no actual searching funded by NASA going on then. By comparison, the Pentagon, three or four decades later, would spend $48 million to build a single mile of seawall in the remote north to protect one of the BMEWS radar support sites against the Arctic Ocean. Your government $$'s at work. This alone was more than 5 times the entire annual budget required to run Arecibo (before it fell to pieces).

In 1982 Proxmire led the Senate to discontinue all federal funding for SETI. Frank Drake nominated Proxmire for membership in the Flat Earth Society, appropriate because he'd filled the infamous Eugene McCarthy's seat when the latter died (--at the age of only 48). After meeting with Carl Sagan (and others), Proxmire agreed to look the other way when some funding was restored in 1983 (the D's had taken back control of the Congress after the 1982 mid-term elections), to build a state-of-the-art multi-channel spectrum analyzer and search with an existing radio telescope, and this continued to bump along at a low level until 1993, when another Senator -- Richard Bryan, a Democrat from Nevado -- got public funding for SETI axed for good: "As of today millions have been spent [$60 million over 23 years, to be exact] and we have yet to bag a single little green fellow. Not a single Martian has said take me to your leader, and not a single flying saucer has applied for FAA approval." If there's anything to be found out there we don't want to know.

The net result was that the classical or Golden Era for SETI, which started in 1959 with the Cocconi & Morrison paper ended about 1979.

[At right: artists conception of a proposed Arecibo sized "BORT" -- Big Orbiting Radio Telescope. The separate ring structure is for blocking radio interference, since the antenna feed looks down towards Earth and its sensitivity profile would slightly spill over the edge of the dish.]

All this was in spite of the large public support for SETI. IOW, there was no real political opposition to SETI until Proxmire discovered he could exploit it for selfish political purposes and score cheap political points. Today there'd probably be a hashtag backlash to make someone like him pay the political price for such assinine antics, especially considering that the War Machine spends an equivalent amount (in today's $$'s) about every 7-8 minutes.

The irony, or course, is that we're still spending vastly larger amounts on the planet's only interstellar quasi-beacons, the high power military radar systems scanning the horizon for incoming Russian (or North Korean) "nuclear-tipped" missles.

In another irony, over about the decade of the 1980's, a radio receiver technology surface area equivalent to the Cyclops array was constructed in the U.S., only it was in the form of backyard satellite TV dishes!

These were first advertised in the 1979 Neiman Marcus catalog for $36K, though by 1985 the price was down to $1,500, and Radioshack was selling a complete system by 1990. There were so many it was once jokingly proposed that they be made the state flower of West Virginia because of the way they'd popped up everywhere. These dishes were eavesdropping on the satellite broadcasts intended as downlinks to various stations around the country that were part of the big broadcasters' and cable systems' networks. Their energy was falling in people's backyards and was otherwise causing the radio frequency equivalent of light pollution (interference), or, if you prefer, was just going to waste.

1,100,000 3-meter diameter antennas have the same total area as Cyclops's thousand 100-meter dishes, and while good numbers are difficult to come by, at their peak there were probably many times this many -- before the satellite broadcasts were scrambled and/or cable TV had reached all the more rural and remote areas of the country, and before technological advances allowed the dishes to shrink in size to about just 1 meter in diameter.

In an early example of hacking and monkey-wrenching, a guy using the moniker Captain Midnight hijacked HBO's signal (1986) for 4½ minutes with a message of protest.

Some may wonder how the advances in technology over the intervening four decades have changed things. Qualitatively they haven't, I don't think. When we did our work, cable TV was the New Thing, and claiming it would take over the world, shortly replacing broadcast TV. It didn't. Even as cable spread during the 1980s, and as satellite TV came online in addition, broadcast TV held on with a third or 40% of the viewership, and I don't think very many broadcast stations went off the air as their signals were taken up on cable TV. It was a BOTH/IF situation, not EITHER/OR.

When digital TV standards replaced NTSC analog, the new system was designed to be backwardly compatible with the existing infrastructure of TV sets -- just as the introduction of color TV in the early 1960s didn't instantly obsolete the tens of millions of B&W sets. These would wear out and get replaced in due time by the newer color sets.

And while I haven't had this confirmed by any TV engineering expert, one gathers the broadcast power is roughly the same as it was when the stations first went up, and that something like half the power is still in the very narrow bandwidth carrier (1 Hz or less) -- the remaining picture and sound information still being spread out at very much lower levels covering millions of hertz of bandwidth.

If TV receiver "front ends" have improved in sensitivity, this simply allows the signal to be received at greater distances without going 'snowy' (analog) or dropping out (digital), rather than really allowing the broadcasters to dial back their power levels significantly. With the steadily increasing population and spreading suburbia, the extra range by better receivers more or less accommodates this growth at no cost to the stations. Some likely have upped their broadcast power, as the technological improvements cut both ways, so an old 50 KW transmitter could be replaced when it wears out with the then current model, which puts out 75 or 100 KW but costs about the same. The relevant factor here is that the cost of electricity to power a station transmitter is minimal compared to the cost of land, buildings, personel, and all the other auxilliary equipment it takes to get "on the air".

One minor change has been the reallocation of UHF channels 51 to 83 from TV broadcasting to cell phone use. The allowed power for UHF stations has also been dropped from 5 megawatts to 1 MW, but back in the 1970s there were not a lot of stations that were up in the 1 MW realm, much less 5 MW. The high-VHF channels have had their top power reduced by ~2x, to 160 kilowatts. So some of the small details our model generated would be slightly changed, but not the overall conclusions.

And while I don't have specific information on the situation for broadcast TV in other parts of the world besides the US, again my impression is the big picture hasn't changed very much -- though TV isn't very good at covering itself, especially regarding technical matters, and especially in other countries.

The one thing that has changed over the intervening four decades is that the search for habitable (and habitated) planets has moved from ground- and radio-based SETI to the planet hunting satellites like Kepler and TESS, which work in the visual part of the spectrum. One good SETI detection would instantly tell us a ton of things, even if the signal or message itself was indecipherable. Now it seems like everyone's intent on going star-by-star the slow way, trying to detect planets around stars, and then maybe whether the finds have an atmosphere that might support life, or show possible anomalies suggesting the presence of possible "biological activity" (whatever that might be), etc. A SETI signal would shortcut this.

In other words, what's happened is we've devolved from doing SETI, looking for radio capable intelligence, to the easier but far less definitive SETH, looking for extra-terrestrial habitabilty -- and maybe SETL, extra-terrestrial life.

Carl Sagan once pondered the question of how a flyby spacecraft could detect there being life here on earth, ignoring both the light pollution from cities on the night side of the planet and all the leaked radio emissions. It turns out cows would be the thing that does it, that makes it doable, since they emit methane, which is unstable in an oxygen rich atmosphere like the one we have. The methane essentially 'burns', oxidizing to CO2, over a timescale of about a decade, and thus disappears if it's not being actively produced and replaced.

There are a few other anomalies like this that might turn up in the detailed analysis of the spectrum of an exo-planet which would point to there being life there, but there are also a world of possible ambiguities that are far more likely, in my opinion.

The measurement of such anomalies or spectral signatures is non- trivial. Just detecting an earth-sized planet going around a star like the sun is difficult enough: when it transits the sun, the earth only blocks about 1/12,000th of the sun's light; this is 0.00837% or all of 0.091 milli-magnitudes. Scientists hate the kind of measurement where one is differencing two large values to detect a miniscule signal, but that's what this amounts to. It can be done, but one has to be very careful and attentive.

And this would be just to detect the earth. Doing spectroscopy on the earth's atmosphere would be a whole 'nuther stretch. If we take the atmosphere to be 20 km high -- the 500 millibar or midpoint level in the atmosphere is at about 18,000 or 20,000 feet, depending on the low and high pressure systems, which is 5.8 km -- then the annulus representing the atmospheric ring around the earth is only 1/67th the area of the earth's disk itself. (It's only two millionths of the area of the sun's disk.) Then, to do spectroscopy, we'd need to take the tiny bit of light from the sun coming through this narrow ring and spread it out into the colors of the rainbow, making it at least 100-1000 times dimmer still, depending on what kinds of spectral lines we'd like to try and resolve and measure. And if all this was done exactly right we might be able to deduce the presence of cows.

There's one other thing that has changed and needs updating, or at least is worth a mention: at the top of "Eavesdropping on the Earth" we quickly dispense with anything in the visual part of the spectrum, on the basis that there's nothing humans do with visible light which compares with the brightness of the sun. Well, technology advances and there are now lasers in the megawatt range that could conceivably outshine the sun by 103 or 104 times (pulsed lasers specifically) at the wavelengths at which they operate. The downside is that lasers illuminate only a very tiny spot on the sky; even if this is enlarged to something like the angular size of the moon you'd have to be in just the right direction to intercept the laser beam. This essentially negates the 103 to 104 gain, and then some, since the entire angular area of the sky is about 2×105 times the angular area of the moon. Nevertheless, people have conducted searches for such laser beams coming in our direction, obviously without any detections to date. The one advantage of visible over radio wavelengths is a much higher data transmission rate, due to the higher frequency, to the tune of 104 to 106 times, though the question still remains why anyone (or thing) would be pointing a laser at us.

Along the same lines, by the early 1990's there had been a number of studies by several groups on the potential for space-based and/or lunar-based optical and IR interferometers. The current European Space Agency's GAIA mission eventually grew out of some of this work. In normal operation, a two-beam interferometer combines the light from two telescopes spaced some distance apart (tens of meteres) in what's called constructive interference. By changing the phase of the wavefront coming from one of the beams through a change in the path length by half a wavelength it's also possible to create destructive interference. Why would anyone want to do this? To dim the light of a star so as to be able to see faint objects like planets very near it. A 1992 review paper by Shao and Colavita states that at 10 parsecs Jupiter would be a 27½ magnitude object, while the earth would be a magnitude fainter; by the definition of the parsec, the earth would be 0.1 arc-seconds from the sun and Jupiter ½ arc-second. At this distance the sun would be magnitude 4¾ and have a diamter of 0.9 milli-arcseconds (mas). As of about 1990, operating interferometers could achieve resolutions of the disks of nearerby supergiant stars to an accuracy of 4-5 mas, though through repeated observation and averaging the formal errors were reduced to ~½ mas, or ~1% of the stars' diameters. So with the longer interferometer baselines achievable on orbit (or the moon) it was thought possible to eventually resolve the disks of the nearer main sequence stars. As well, with destructive intereference the star could be nulled and the vicinity of the nearer stars searched for exoplanets.

All this was a few years before the first exo-planet was actually discovered. There are two main limitations on how deep of a nullification can be achieved and thus how faint of a nearby object could be detected. The first is just that if the baseline is sufficient to resolve the disk of the star then the cancellation is not complete over its entire disk; the center of the disk can be completely nulled out but the star's limb only partially so (or vice versa).

The other limitation is due to scattered light from minute surface irregulaties in the interferometer optics. But even so, with then currently available mirrors and beam-splitters it was estimated the star nullification achievable might be as much as 15 magnitudes (or more). With a contrast then of less than 10 magnitudes it would be possible to detect Jupiters and earths with not overly long integration times. So maybe the earth's faintness next to the sun at visible wavelengths would not be insurmountable to an extraterrestrial astronomer. Of course this would be due to reflected sunlight, not anything humans are doing. But it does suggest that anyone with a high-powered laser hoping to be seen at interstellar distances might want to direct it between about 70° and 120° from the sun, if it's pointed within 20° or 30° of the ecliptic, because then the earth will be at its largest angular separation from the sun and thus more easily visible. Otherwise, one would do better pointing it at higher ecliptic latitudes where the projection effects are lessened and earth is always a decent angle away from the sun for the distance.

Want to investigate all this more? Read Astronomical Searches for Earth-Like Planets and Signs of Life, by Neville Woolf & J. Roger Angel; 1998 Annual Reviews of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Along the way in school I took various classes from several illustrious astronomers:

Robert ("Bob") Williams, who would often regale us with accounts

of his weekend and break trips backpacking in the Grand Canyon,

taught ionization nebula, from Osterbrock's book on the subject.

This included not just class HII regions like the Orion Nebula or

M20, but other emission line spectra objects, like Seyfert galaxies

and quasars (his speciality). He moved on from Tucson several years

later to become the director of the Cerro Tololo Inter-American

Observatory (1986-93), home of the 4-meter telescope that's a twin

of the one on Kitt Peak. From there he then became the director of

the Space Telescope Science Institute (at Johns Hopkins), from 1993

to 1998, where, with his director's discretionary time on the

telescope (10%), he made the

Hubble Deep Field observations in 1995. He also gave some of

discretionary time on HST in 1996 to the two groups working on

supernovae which got the Nobel Prize for the discovery of "dark

energy" (the increasing expansion rate of the universe). He followed

up that job by being President the IAU from 2009–2012, which was

following the Pluto demotion debacle.

If you've got 90 minutes you can watch a lecture on

"The Universe as Seen Through the Hubble Space

Telescope" delivered January 22, 1998, at the University of

Washington. (scroll down ~¾th the way to the bottom of the

page since it's the last in the list of Video Lectures.)

Roger Angel taught optics from a phonebook sized and largely impenetrable compendium on the topic (Longhurst), and was famous for his stash of black masking tape, which no one else had ever seen or heard of; he'd use it in place of screws to hold all the instruments and other gadgets he was making for the various telescopes together. A decade or more later he got going in the spun mirror casting business, a method for making large monolithic telescope mirrors that are substantially lighter and stiffer (and had better thermal characteristics) than solid 'blanks', as they're called, like the Palomar 200", and require much less rough grinding to figure. Numerous such mirrors, ranging in size from 1.8 to 8.4 meters in diameter have been installed in telescopes around the world, including the Giant Magellan Telescope. He was a 1996 MacArthur Fellow and twenty years later was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Perhaps the most famous one was

Vera Rubin. She spent her career at the Carnegie

Institution, which doesn't have degree programs or classes, so not many

can say they were one of her students. She came to visit for a quarter at

the grad school I was at and I took her class. (It was easy because, since

I don't think she'd ever put together or taught an entire class before,

she started at a very broad and basic level, so it was more like an under-

grad course.) This was not long after she first became well known in the

field of galaxies for a paper with Ford & Thonnard on spiral galaxy

rotation and galaxy masses (Astrophysical Journal Letters, 1978), which

pushed the rotation curves in the visual part of the spectrum out to the

faintest level then yet achieved, finding that they were either flat or

still rising, whereas at some point it had been thought they had to start

to fall off in what's called a Keplerian (1/r½) fashion.

This meant the masses determined were only lower limits, because the

outer edges of large spirals still hadn't found, and, as well, that the

increasing mass-to-light ratios suggested an increasing presence of

'dark matter'.

Probably the highlight of the course was getting to see several of her

spectrograms, glass plate negatives made with their image tube (aka night

vision) spectrograph on the Kitt Peak 4-meter telescope. I even got to

pick one up and hold it up to the light. I was struck by how small it was

-- only about 10 cm (2½") square -- and how tiny the little streak

of light representing the galaxy's spectrum was. I'd been scanning and

digitizing 8"x10" prime focus glass plate negatives made with the Cerro

Tololo 4-meter telescope, and they were absolutely huge by comparison.

I believe the photo of her at the link at the top was taken of her with

this equipment in 1977-78.

Next would be Donald Brownlee, who'd only been at the University of Washington a little while when I was in my first year of astronomy major courses. He subbed my planetary sciences class one day, when the professor unexpectedly couldn't make it. We basically got a tour of his space dust lab rather than a lecture. At that time he was analyzing meteoritic dust collected well up in the stratosphere by re-purposed, high-flying U2 spy-planes. They basically put a piece of sticky paper out the window. At 80,000-100,000 feet up the air is so clean that a large proportion of the dust particles are from burned up meteors. Later he'd go on to be principal investigator for the NASA Stardust sample return spacecraft to Comet 81P/Wild (aka Wild 2), which took from 1999 to 2006, the actually comet flyby occurring on Jan 2, 2004. It used aerogel to collect particles rather than flypaper. Brownlee's also co-author with Peter Ward of the 2004 book The Life and Death of Planet Earth, which put a new perspective on the Drake Equation, making the case that there's not only a Goldilocks / habitable zone spatially but also one temporally, and that the earth may already be post-peak.

And I have to mention George Wallerstein, whose stature has grown

over the decades. He was a grad student at Cal Tech, arriving the

same month (Sept. 1953) as Hubble and Millikan (Cal Tech's founder)

died. After his Ph.D he was an instructor and then assistant professor

at UC/Berkeley, but got hired away just as he was gaining tenure to

to be part of a newly expanding University of Washington astronomy

department. He was chairman when I was an undergrad there. His

expertise is in high resolution spectroscopy of stars, stellar

abundances and nucleosynthesis, and the more unusual and mystifying

sorts of variable stars. He could get occasional time on the 200"

telescope, bright-of-the-moon, because he wasn't doing edge-of-the-universe

stuff, but rather high dispersion spectroscopy on typically brighter

objects. He used the HST to study interstellar lines in supernova

remnants (in the UV). I took two courses from him my senior year,

one on stellar interiors -- using Martin Schwartzchild's then twenty

year-old book on the subject, which never-the-less was very good on

the timeless fundamentals -- and the other on the interstellar

medium (with no text). He also oversaw my senior thesis project

on white sky color photography, and generously made the

Manastash Ridge Observatory 30" facilities

available to me to make this possible even after I'd technically

already graduated.

Classic George W: The Metallicity and Lithium Abundances of

the Recurring Novae T CrB and RS Oph [note the connection

with SN Ia].

Dr. Lowell S. Brown, professor of Physics at the University of

Washington and noted theoretical particle physics expert. I took

honors freshman physics from him in the Fall of 1974, when he was

in almost daily contact (right before class) via long-distance

phone calls, when these expensive, with the people at SLAC

(Stanford Linear Accelerator Center) when they were discovering

the J/Ψ particle, for which they got

the Nobel Prize in 1976. This is referred to as

"the November Revolution" (11/11/1974) because it fairly cinched the

case for the existence of quarks.

I don't know what it was about Dr. Brown but he was the only person

I've known who seemed like a real genius. I've crossed paths with a

lot of smart people, but he was different in some way that's difficult

to put into words.

Dr. Erika Böhm-Vitense. Another Univ. of Wash. professor, who I had for my first "real" astronomy course as a major, meaning one centered on stars, especially stellar atmospheres, radiation transfer, and things like the Saha equation. This was at the end of the first/junior year, the first two of the three courses being celestial mechanics and the solar system (planets, not the sun). It was only decades later that I'd see a pioneering paper (1958, I think) by her on convection in stars referenced in various papers; we didn't cover that since it would be under stellar interiors -- the next semester (first as a senior).

Backstory #3: About the time Isaac Asimov and an interest in supernovae cost me a science college scholarship.

Back to: [ Main VISNS Page || Backstory #1]